Escape from New York

| Escape from New York | |

|---|---|

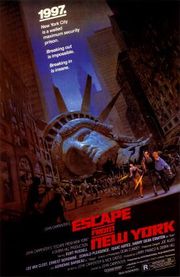

Theatrical release poster |

|

| Directed by | John Carpenter |

| Produced by | Larry J. Franco Debra Hill |

| Written by | John Carpenter Nick Castle |

| Starring | Kurt Russell Lee Van Cleef Ernest Borgnine Donald Pleasence Isaac Hayes Harry Dean Stanton Adrienne Barbeau Season Hubley Tom Atkins |

| Music by | John Carpenter Alan Howarth |

| Cinematography | Dean Cundey Jim Lucas |

| Editing by | Todd Ramsay |

| Distributed by | AVCO Embassy Pictures |

| Release date(s) | United States: July 10, 1981 |

| Running time | 99 minutes |

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

| Budget | $6,000,000 (est.)[1] |

| Gross revenue | $50,000,000 (Worldwide)[2] |

| Followed by | Escape from L.A. (1996) |

Escape from New York is a 1981 science fiction action film directed and scored by John Carpenter. He also co-wrote the screenplay with Nick Castle. The film is set in the near future in a crime-ridden United States that has converted Manhattan Island in New York City into a maximum security prison. Ex-soldier and legendary fugitive "Snake" Plissken (Kurt Russell) is given 24 hours to find the President of the United States, who has been captured by inmates after Air Force One crashed on the island.

Carpenter originally wrote the film in the mid-1970s as a reaction to the Watergate scandal, but no studio wanted to make it because Carpenter proved unable to articulate just how this film could relate to the Watergate scandal. After the success of Halloween, he had enough influence to get the film made and shot most of it in St. Louis, Missouri, where significant portions of the city were used in place of New York City.[3]

The film's total budget was estimated to be US$6 million.[1] It was a commercial hit, grossing over $50 million worldwide.[2] It has since developed its own cult following, particularly around the anti-hero Plissken. A sequel, Escape from L.A., was released in 1996.

Contents |

Plot

In a dystopian 1997, World War III is nearing an end. Both the United States and Soviet Union have suffered greatly in the conflict and are looking for a peaceful resolution. Due to a nationwide crime increase of 400%, Manhattan was turned into one giant maximum security prison in 1988. Surrounded by a 50 foot containment wall, and mines on all bridges and waterways, nobody is allowed in the prison, not even guards. Because there are no guards inside the prison there is only "prisoners and the worlds they have made. The rules are simple: once you go in, you don't come out. "

Travelling to a three-way summit between the United States, the Soviet Union and China, Air Force One, the plane of the President of the United States, is hijacked by a lone member of a left-wing revolutionary organization, called the National Liberation Front of America, opposed to the government. The militant terrorist,[4] disguised as a stewardess, crashes the plane into Manhattan, but the President (Donald Pleasence) is placed in an escape pod and survives. The inmates quickly find him and take him hostage, cutting off one of his fingers to present as evidence and ordering all United States Police Force officers to leave Manhattan immediately or they will kill him.

USPF Commissioner Bob Hauk (Lee Van Cleef) offers a deal to a newly arrived prisoner, an infamous special forces-soldier-turned-criminal named "Snake" Plissken (Kurt Russell) who was apprehended after robbing the Federal Reserve Depository. If Snake rescues the president, and retrieves a cassette tape that contains important information on nuclear fusion, Hauk will give him a full pardon. However, Plissken must complete his mission before the international summit that the President was due to attend, which begins in 24 hours. By the time Plissken has reluctantly agreed to attempt the rescue, Hauk has discreetly (Snake is told he is being injected with something routine) had him injected with microscopic explosives that will rupture his carotid arteries once 24 hours have passed. The explosives cannot be defused until within 15 minutes before detonation, as a way of ensuring that Snake does not abandon his mission and escape, or find another way to remove them. If he returns with the President and the tape in time for the summit, Hauk will save him. Snake promises to kill Hauk when he returns.

Snake covertly lands atop the World Trade Center in a glider, and then locates the hijacked plane wreckage and the escape pod, but the President is gone. Snake tracks the President's life-monitor bracelet signal to the basement of a dilapidated theater, only to find it on the wrist of an incoherent old man (George "Buck" Flower). He meets a friendly inmate nicknamed "Cabbie" (Ernest Borgnine), who offers to help. Cabbie takes Snake to see Harold 'Brain' Close (Harry Dean Stanton), a savvy and well-educated inmate who has made the New York Public Library his personal fortress. Brain, who knows Snake from some heists they did in the past, tells Snake that the self-proclaimed "Duke of New York" (Isaac Hayes), the leader of the Gypsies, the largest and most powerful gang in Manhattan, has the President and plans to lead a mass escape across the mined and heavily guarded 69th Street Bridge, using the President as a human shield. When the Duke unexpectedly arrives to obtain a diagram of the bridge's land mines, Snake forces Brain and his girlfriend Maggie (Adrienne Barbeau) to lead him back to the Duke's compound at Grand Central Station. Snake finds the President being held in a railroad car, but his rescue fails and he is captured after Brain apparently betrays Snake.

While Snake is forced to fight with a giant brute (Ox Baker), Brain and Maggie trick the Duke's men into letting them have access to the President. After killing the guards, they free the President and flee to Snake's glider. Meanwhile, Snake defeats his opponent. When the Duke learns the President has escaped with Brain, he is furious, and he rounds up his gang to chase them down. In the confusion, Snake slips away and manages to catch up with Brain, Maggie and the President at the glider, but during their attempted getaway, a gang of inmates push it off the building. Snake and the others soon find Cabbie, and Snake takes the wheel of his cab, heading for the bridge. When Cabbie reveals that he has the nuclear fusion tape, the President demands it, but Snake takes it.

With the Duke chasing in another car, Snake and the others drive over the mine-strewn bridge. After the taxi hits a land mine, the cab is destroyed and Cabbie is killed. As the others flee on foot, Brain is killed by a mine and Maggie refuses to leave him. She attempts to hold off the Duke's car by firing at him with a revolver, but he crashes into Maggie and kills her, and continues on foot. Snake and the President reach the containment wall, and the guards raise the President on a rope. The Duke then attacks Snake, but the President shoots the Duke, killing him. Snake is then lifted to safety, and the explosives implanted in his body are deactivated with seconds to spare.

As the President prepares for a televised speech, he distractedly thanks Snake for saving him. Snake asks him how he feels about the people who died saving his life, but the President only offers half-hearted regret that visibly disgusts Snake. The President's speech commences and he offers the content of the cassette to the summit; but to the President's embarrassment, the tape has been switched for a cassette of the swing song "Bandstand Boogie" (the theme from American Bandstand), Cabbie's favorite song. After Snake is pardoned, he decides he will not kill Hauk at this time and leaves the prison, tearing apart the all-important nuclear fusion tape and smiling as he leaves.

Cast

- Kurt Russell as "Snake" Plissken

- Lee Van Cleef as Commisioner Bob Hauk

- Ernest Borgnine as Cabby

- Donald Pleasence as the President of the United States of America

- Isaac Hayes as The Duke of New York

- Harry Dean Stanton as Harold 'Brain' Close

- Adrienne Barbeau as Maggie

- Season Hubley as Tramp Woman

- Tom Atkins as Camp Henchman

- Ox Baker as Giant Brute

- George "Buck" Flower as Incoherent Old Man

Development

Carpenter originally wrote the screenplay for Escape from New York in 1976, in the aftermath of the Watergate scandal. Carpenter said, "The whole feeling of the nation was one of real cynicism about the President. I wrote the screenplay and no studio wanted to make it" because, according to Carpenter, "it was too violent, too scary, too weird."[5] He has also been inspired by the film Death Wish which was very popular at the time. He did not agree with this film's philosophy but liked how it conveyed "the sense of New York as a kind of jungle, and I wanted to make a science fiction film along these lines".[6]

Casting

Avco-Embassy Pictures, the film's financial backer, preferred either Charles Bronson or Tommy Lee Jones to play the role of "Snake" Plissken to Carpenter's choice of Kurt Russell, who was trying to overcome his "lightweight" screen image which arose from his roles in several Disney comedies. Carpenter refused to cast Bronson on the grounds that he was too old, and because he worried that he could lose directorial control over the picture with an experienced actor. At the time, Russell described his character as "a mercenary, and his style of fighting is a combination of Bruce Lee, The Exterminator, and Darth Vader, with Eastwood's vocal-ness."[7] All that matters to Snake, according to the actor, is "the next 60 seconds. Living for exactly that next minute is all there is."[8]

Pre-production

Carpenter had just made Dark Star but no one wanted to hire him as a director, so he assumed that he would make it in Hollywood as a screenwriter. The filmmaker went on to do other films with the intention of making Escape later. After the success of Halloween, Avco-Embassy signed him and producer Debra Hill to a two-picture deal. The first film from this contract was The Fog. Initially, the second film that he was going to make to finish the contract was The Philadelphia Experiment, but because of script-writing problems, Carpenter rejected it in favor of this project. However, Carpenter felt that something was missing and recalls, "This was basically a straight action film. And at one point, I realized it really doesn't have this kind of crazy humor that people from New York would expect to see."[9] He brought in Nick Castle, a friend from his film school days at University of Southern California who also played "The Shape" in Halloween. Castle invented the Cabbie character and came up with the film's ending.[10]

The film's setting proved to be a potential problem for Carpenter, who needed to create a decaying, semi-destroyed version of New York City on only a shoe-string budget. He and the film's production designer, Joe Alves rejected shooting on location in New York City because it would be too hard to make it look like a destroyed city. Carpenter suggested shooting on a movie back lot but Alves nixed that idea "because the texture of a real street is not like a back lot."[11] They sent Barry Bernardi, their location manager (and also associate producer), "on a sort of all-expense-paid trip across the country looking for the worst city in America," producer Debra Hill remembers.[11]

Bernardi suggested East St. Louis, Illinois, because it was filled with old buildings "that exist in New York now, and [that] have that seedy run-down quality" that the team was looking for.[12] East St. Louis, sitting across the Mississippi River from the more prosperous St. Louis, Missouri, had entire neighborhoods burned out in 1976 during a massive urban fire. Hill said in an interview, "block after block was burnt-out rubble. In some places there was absolutely nothing, so that you could see three and four blocks away."[11] As well, Alves found an old bridge to double for the "69th St. Bridge". The filmmaker purchased the Old Chain of Rocks Bridge for one dollar from the government and then gave it back to them for a dollar, "so that they wouldn't have any liability," Hill remembers.[11] Locations across the river in St. Louis, Missouri were also used, including Union Station and the Fox Theater, both of which have since been renovated.[13]

Production

Carpenter and his crew persuaded the city to shut off the electricity to ten blocks at a time at night. The film was shot from August to November 1980. It was a tough and demanding shoot for the filmmaker as he recalls. "We'd finish shooting at about 6 am and I'd just be going to sleep at 7 when the sun would be coming up. I'd wake up around 5 or 6 pm, depending on whether or not we had dailies, and by the time I got going, the Sun would be setting. So for about two and a half months I never saw daylight, which was really strange."[9]

The gladiatorial fight to the death scene between Snake and Slag (played by professional wrestler Ox Baker) was filmed in the Grand Hall at St. Louis Union Station. Russell has stated, "That day was a nightmare. All I did was swing a [spiked] bat at that guy and get swung at in return. He threw a trash can in my face about five times ... I could have wound up in pretty bad shape."[14] In addition to shooting on location in St. Louis, Carpenter also shot parts of the film in Los Angeles. Various interior scenes were shot on a soundstage; the final scenes were shot at the Sepulveda Dam, in Sherman Oaks. New York also served as a location, as did Atlanta, in order to utilize their then futuristic-looking rapid-transit system.[15]

When it came to shooting in New York City Carpenter managed to persuade the city officials to grant access to Liberty Island. "We were the first film company in history allowed to shoot on Liberty Island at the Statue of Liberty at night. They let us have the whole island to ourselves. We were lucky. It wasn't easy to get that initial permission. They'd had a bombing three months earlier and were worried about trouble."[16]

Carpenter was interested in creating two distinct looks for the movie. "One is the police state, high tech, lots of neon, a United States dominated by underground computers. That was easy to shoot compared to the Manhattan Island prison sequences which had few lights, mainly torch lights, like feudal England."[16]

Certain matte paintings were rendered by James Cameron, who was at the time a special effects artist with Roger Corman's New World Pictures.

As Snake pilots the glider into the city there are three screens on his control panel displaying wireframe animations of the landing target on the World Trade Center and surrounding buildings. What appears on those screens was not computer generated. Carpenter wanted hi-tech computer graphics which were very expensive at the time, even for such a simple animation. To get the animation he wanted the effects crew filmed the miniature model set of New York City they used for other scenes under black light with reflective tape placed along every edge of the model buildings. Only the tape shows up and appears to be a 3D wireframe animation.[17]

Reception

Escape from New York grossed $25.2 million in American theatres in summer 1981 with a comparable gross in the international market, resulting in a $50 million box office, a revenue-production ratio of almost 7:1.[2] The film received generally positive reviews. It received a rating of 81% on Rotten Tomatoes. Newsweek magazine commented on Carpenter, saying, "[He has a] deeply ingrained B-movie sensibility - which is both his strength and limitation. He does clean work, but settles for too little. He uses Russell well, however."[18] In Time magazine, Richard Corliss wrote, "John Carpenter is offering this summer's moviegoers a rare opportunity: to escape from the air-conditioned torpor of ordinary entertainment into the hothouse humidity of their own paranoia. It's a trip worth taking."[19] Vincent Canby, in his review for the New York Times, wrote, "[The film] is not to be analyzed too solemnly, though. It's a toughly told, very tall tale, one of the best escape (and escapist) movies of the season."[20] However, in his review for the Chicago Reader, Dave Kehr, wrote "it fails to satisfy–it gives us too little of too much."[21]

Cyberpunk pioneer William Gibson credits the film as an influence on his novel Neuromancer. "I was intrigued by the exchange in one of the opening scenes where the Warden says to Snake 'You flew the Gulffire over Leningrad, didn't you?' It turns out to be just a throwaway line, but for a moment it worked like the best SF where a casual reference can imply a lot."[22] Popular videogame director Hideo Kojima has referred to the movie frequently as an influence on his work, in particular the Metal Gear series. The character Solid Snake is strongly based on Snake Plissken. In Metal Gear Solid 2: Sons of Liberty Snake actually uses the alias "Pliskin" to hide his real identity during the game.[23] J.J. Abrams, producer of the 2008 film Cloverfield, mentioned that a scene in his film, which shows the head of the Statue of Liberty crashing into a New York street, was inspired by the poster for Escape from New York.[24] Empire magazine ranked Snake Plissken #71 in their "The 100 Greatest Movie Characters" poll.[25]

Soundtrack

Media

DVD releases

Escape from New York was released on DVD twice by MGM (USA), and once by Momentum Pictures (UK). One MGM release is a barebones edition containing just the theatrical trailer. Another version is the Collector's Edition, a two-disc set featuring a remastered transfer with a 5.1 audio track, two commentaries (one by John Carpenter and Kurt Russell, another by producer Debra Hill and Joe Alves), a making-of featurette, the first issue of a comic book series titled John Carpenter's Snake Plissken Chronicles, and a ten-minute deleted opening sequence.[26]

MGM's special edition of the 1981 film was not released until 2003 because the original negative had disappeared. The workprint containing deleted scenes finally turned up in the Hutchinson, Kansas salt mine film depository. The excised scenes feature Snake Plissken robbing a bank, introducing the character of Plissken and establishing a backstory. Director John Carpenter decided to add the original scenes into the special edition release as an extra only: "After we screened the rough cut, we realized that the movie didn't really start until Snake got to New York. It wasn't necessary to show what sent him there."[27] The film has also been released on the UMD format for Sony's Playstation Portable.[28]

Novelization

In 1981, Bantam Books published a movie tie-in novelization written by Mike McQuay that adopts a lean, humorous style reminiscent of the film. The novel is significant because it includes scenes that were cut out of the film, such as the Federal Reserve Depository robbery that results in Snake's incarceration. The novel also provides motivation and backstory to Snake and Hauk — both disillusioned war veterans — deepening their relationship that was only hinted at it in the film. The novel explains how Snake lost his eye during the Battle for Leningrad in World War III, how Hauk became warden of New York, and Hauk's quest to find his crazy son who lives somewhere in the prison. The novel also fleshes out the world that these characters exist in, at times presenting a future even bleaker than the one depicted in the film. The book explains that the west coast is a no-man's land, and the country's population is gradually being driven crazy by nerve gas as a result of World War III.[29]

Remake

Scottish actor Gerard Butler was close to signing a deal where he would play Snake Plissken in a remake of Carpenter's movie.[30] Neal Moritz was to produce and Ken Nolan was to write the screenplay which would combine an original story for Plissken with the story from the 1981 movie, although Carpenter has hinted that the film might be a prequel.[31]

New Line Cinema (one-time video distributor of the original) acquired the rights to the film from co-rights holder StudioCanal, who will control the European rights, and Carpenter, who will serve as an executive producer and said, "Snake is one of my fondest creations. Kurt Russell did an incredible job, and it would be fun to see someone else try."[32] Russell has also commented on the remake and on the casting of Butler as Plissken, saying, "I will say that when I was told who was going to play Snake Plissken, my initial reaction was 'Oh, man!' [Russell winces]. I do think that character was quintessentially one thing. And that is, American."[33] Len Wiseman was attached to direct but he dropped out of the project and rumors were that Brett Ratner would helm the film.[34] Since Ratner has not formally committed to the new project, the identity of the director is as yet unclear. The studio has brought Jonathan Mostow in to rewrite, with an option to direct. In addition, Gerard Butler has bowed out of his role claiming "creative differences".[35] Allan Loeb wrote currently the script for the New Line Cinema project.[36]. Breck Eisner has been announced as the director of the remake. The film will not feature a post apocalyptic New York like the original did, rather the New York in the new film will have been built after the bomb.[37]

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 "Escape from New York (1981) - Box office / business". http://www.imdb.com/title/tt0082340/business. Retrieved 2007-05-04.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 "Escape from New York". Box Office Mojo. May 4, 2007. http://www.boxofficemojo.com/movies/?id=escapefromnewyork.htm. Retrieved 2007-05-04.

- ↑ Phantom of the Movies (2003-12-11). "Escape From New York rushes into a DVD world". Washington Weekend (Washington Times): pp. M24.

- ↑ http://www.dvdfile.com/reviews/dvdreviews/30823-escape-from-new-york

- ↑ Yakir, Dan (October 4, 1980). "'Escape' Gives Us Liberty". New York Times. http://www.theofficialjohncarpenter.com/pages/press/nypost801014.html. Retrieved 2007-03-10.

- ↑ Maronie, Samuel J. (April 1981). "On the Set with Escape from New York". Starlog. http://www.sphosting.com/theefnypage/pressontheset.htm. Retrieved 2007-03-10.

- ↑ Hogan, Richard (1980). "Kurt Russell Rides a New Wave in Escape Film". Circus magazine. http://www.theofficialjohncarpenter.com/pages/press/circus1980.html. Retrieved 2007-03-10.

- ↑ Goldberg, Lee (July 1986). "Kurt Russell — Two-Fisted Hero". Starlog.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 Swires, Steve (July 1981). "John Carpenter". Starlog.

- ↑ Ryan, Desmond (1984-07-14). "Launch of a giddy fantasy a director reaches for the stars with computer aid". The Philadelphia Inquirer: p. D01.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 11.2 11.3 Beeler, Michael. "Escape from N.Y.: Filming the Original". Cinefantastique.

- ↑ Maronie, Samuel J. (May 1981). "From Forbidden Planet to Escape from New York: A candid conversation with SFX & production designer Joe Alves". Starlog. http://www.theofficialjohncarpenter.com/pages/press/starlog8105.html. Retrieved 2007-03-10.

- ↑ Williams, Joe (2005-04-17). "Show Me the movies". St. Louis Post-Dispatch: p. C1.

- ↑ Naha, Ed (November 1981). "Escape From New York". Future Life (#30). http://www.theefnylapage.com/articles/Future%20Life%201981.pdf.

- ↑ Berger, Jerry (1995-02-05). "St. Louis Q&A". St. Louis Post-Dispatch: p. 17.

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 Osborne, Robert (October 24, 1980). "On Location". Hollywood Reporter. http://www.theofficialjohncarpenter.com/pages/press/reporter801024.html. Retrieved 2007-03-10.

- ↑ Atkins, Tom; Barbeau, Adrienne. (2003). Escape from New York (Special Edition).

- ↑ "A Helluva Town". Newsweek. July 27, 1981. http://www.theofficialjohncarpenter.com/pages/press/newsweek810727.html. Retrieved 2007-05-30.

- ↑ Corliss, Richard (July 13, 1981). "Bad Apples". Time. http://www.theofficialjohncarpenter.com/pages/press/time810713.html. Retrieved 2007-05-30.

- ↑ Canby, Vincent (July 10, 1981). "Escape from New York". New York Times. http://www.theofficialjohncarpenter.com/pages/press/nytimes810710.html. Retrieved 2007-05-30.

- ↑ Kehr, Dave. "Escape from New York". Chicago Reader. http://onfilm.chicagoreader.com/movies/capsules/3169_ESCAPE_FROM_NEW_YORK. Retrieved 2008-01-29.

- ↑ McCaffery, Larry (1992). "Storming the Reality Studio: A Casebook of Cyberpunk and Postmodern Science Fiction". Duke University Press. http://project.cyberpunk.ru/idb/gibson_interview.html. Retrieved 2008-01-11.

- ↑ SEAL: I'm not an enemy. Calm down. My name is S... My name is Pliskin. Iroquois Pliskin, Lieutenant Junior Grade. (Metal Gear Solid 2: Sons of Liberty, Konami, 2001)

- ↑ Eberson, Sharon (2008-01-04). "Commentary: Filmmakers enjoy laying waste to New York". Pittsburgh Post-Gazette.

- ↑ "The 100 Greatest Movie Characters". Empire. http://www.empireonline.com/100-greatest-movie-characters/default.asp?c=71. Retrieved 2008-12-02.

- ↑ Netherby, Jennifer (2003-08-25). "Escape to a special edition". Video Business (Reed Business Information) 23 (34): 8.

- ↑ Hulse, Ed (2003-11-24). "A newfound Escape". Video Business (Reed Business Information) 23 (47): 33. ISSN: 0279-571X.

- ↑ "Escape From New York (UMD Video For PSP)". Wal-Mart. http://www.walmart.com/catalog/product.do?product_id=4592016. Retrieved 2008-08-28.

- ↑ McQuay, Mike (May 1981). Escape from New York. Bantam Books. ISBN 0-553-25375-1.

- ↑ Fleming, Michael (March 13, 2007). "Butler has Escape plan". Variety. http://www.variety.com/article/VR1117961020.html. Retrieved 2007-06-07.

- ↑ Epstein, Daniel Robert (March 20, 2007). "John Carpenter". SuicideGirls.com. http://suicidegirls.com/interviews/John+Carpenter/. Retrieved 2007-03-23.

- ↑ Kit, Borys (March 16, 2007). "New Line cuffs 'Escape' redo". Hollywood Reporter. http://www.hollywoodreporter.com/hr/content_display/film/news/e3i880911115a741b4126f3d582f7183c25. Retrieved 2007-03-16.

- ↑ Nashawaty, Chris (March 20, 2007). "Remake the Snake?". Entertainment Weekly. http://www.ew.com/ew/article/0,,20015465,00.html. Retrieved 2007-03-23.

- ↑ Billington, Alex (October 29, 2007). "Brett Ratner is NOT Directing the Escape from New York Remake?! UPDATED — Gerard Butler Out Too!". First Showing. http://www.firstshowing.net/2007/10/29/brett-ratner-is-not-directing-the-escape-from-new-york-remake/. Retrieved 2007-11-05.

- ↑ Fleming, Michael (October 29, 2007). "Butler escapes New York remake". Variety. http://www.variety.com/article/VR1117975061.html?categoryid=13&cs=1&query=%22Escape+from+New+York%22. Retrieved 2007-11-05.

- ↑ First Details: Escape From New York Remake Hits the Fast Track

- ↑ "Breck Eisner Talks Escape From New York". The Film Stage. June 22, 2010. http://thefilmstage.com/2010/06/23/breck-eisner-talks-about-escape-from-new-york-will-timothy-olyphant-play-snake. Retrieved June 22, 2010.

External links

- Escape from New York at the Internet Movie Database

- Escape from New York at Allmovie

- Escape from New York at Rotten Tomatoes

- Escape from New York at Official John Carpenter's Website

|

|||||||||||||||||